Providing a Semantic API

A StackOverflow refactoring.

This is part of a series of posts where I refactor code from StackOverflow questions, with a discussion of the changes. One of the great things about JavaScript is how scalable it is. You can start with a simple script, and there is nothing wrong with that. Usually these posts are about refactorings other than what the questioner asked about, and would be out of scope for the SO answer. There is nothing wrong with code that runs, and “There is no such thing as good coding, only good refactoring”.

A Semantic API is “an interface that provides information about usage of the interface” (my definition). It can be through method naming, parameter naming, JS Doc comments, TypeScript typings, or (best) all of the above.

The meaning of “semantics”, according to the Oxford Dictionary:

The branch of linguistics and logic concerned with meaning.

Computer programming is an exercise in applied linguistics. It is precisely specifying the execution of operations to transform matter through the utterance of magic spells.

Writing code that the computer can understand (and that executes correctly) is only one level of the practice of Computer Programming. As Martin Fowler puts it:

Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand.

Providing a Semantic API is part of improving the developer ergonomics, or Dev UX, of your code.

An API is an Application Programming Interface. Although it has come to refer to REST APIs and other external interfaces, every function that you write has an API. If you write libraries that are reused by other developers, as I do with the Zeebe Node.js client, paying careful attention to developer ergonomics is important.

But even if you don’t write libraries, every function that you write is potentially consumed by other developers working on the code base - and minimally by at least one - you.

The Question

Here is the original code from StackOverflow:

I refactored the global variable previously, in the post “Avoiding global mutable state in Browser JS”. This time we are going to refactor the member function to improve the API ergonomics.

Naming

The importance of naming to reduce cognitive load and increase the comprehensibility of your code (both for you and for others) cannot be overstated. See this previous article for more detail.

In the case of this function, we can see looking at the reference to this inside member that this function is intended to be called with the new keyword, to return an instance.

We can signal this using naming by convention. If we make all “newable” objects in the codebase start with a capital letter we communicate information about the function through the name - semantic naming.

First Refactor

So, the first refactor:

I changed the name of the function to Member. If you are disciplined about using this as a naming convention, then any consumers of the Member function know automatically that it must be newed.

This reduces the chances of a bug like this creeping into your code:

const memObj1 = member("m001", "123")

I changed the property name from pwd to password to match the function parameter name. This allows programmers consuming this API to reuse the naming. Forcing them to mentally map a different property from the parameter name is friction that will make using the API unpleasant for them.

I also changed var to const. This is also semantics. var communicates to the machine and to other programmers “I intend that the value of this assignment change over the course of execution. Do not rely on the value of this assignment”, forcing them to reason across the codebase about its eventual value.

const, on the other hand, communicates “this is an immutable assignment”. The machine will throw if you accidentally attempt a mutation, and other programmers do not need to read code between the assignment and an eventual use, later in the codebase, to know what is going on.

I also changed the name of memArray to GlobalMembersArray. This is not a newable object, but the prefix Global, by convention, tells me that it is a global object, and suffix Array tells me that it is an array - anywhere that I encounter it in the code. See this article for a full refactor of this variable.

Finally, I changed the name of memObj1 to member1. It is a small change, but it increases the overall comprehensibility of the code.

Second Refactor

The function as it stands now communicates little information about its parameters.

Fortunately, they are well named, so by looking at the function signature we can see what they are.

When writing code that calls the function in a good IDE, we will see the function signature, and know to call it with two arguments - and we will see the names of the parameters that these arguments will be applied to.

However, when we are reading the codebase, that information is lost:

const member1 = Member("m001", "123")

We have no information here about the meaning (the semantics) of the arguments at this point in the code.

An improvement to the signature of the Member function is to use an object with named keys:

With a very small refactor of the function signature - the addition of two characters: {} - we now have information about the arguments passed to it everywhere in the application.

This style of function signature uses ES6 destructuring assignment to take an anonymous object and immediately destructure the named properties of the object into the local variables id and password in the scope of the function.

We get two things from this:

- Greater protection against mixing up the arguments we pass in. It is easy to do:

new member("pwd", "001"), less easy to mistakenly donew Member({id: "pwd", password: "001"}). - We now have information about the function signature and the semantics of the call everywhere we see it in the codebase.

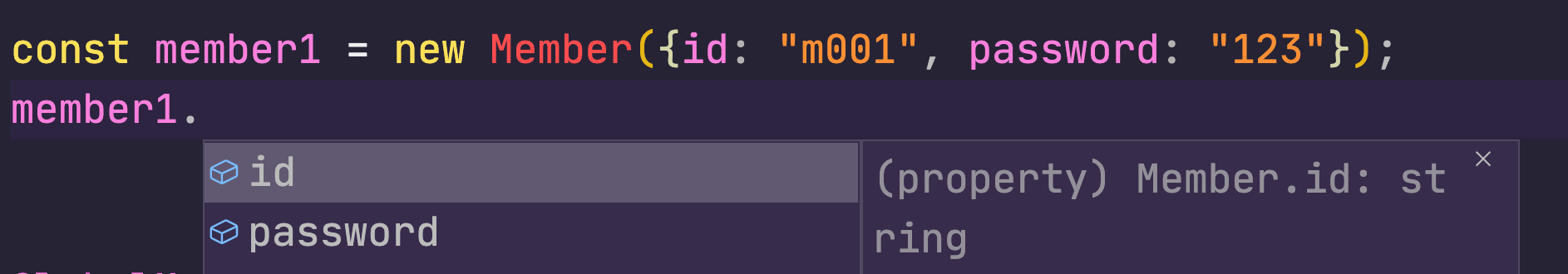

Additionally, if you are using TypeScript with VSCode, you can get autocompletion for the parameters with Ctrl-Space.

#winning

The next level

You could stop here, and it is a significant improvement.

You can take it to the next level, though, by supplying JSDoc comments for the function. JSDoc is a human- and machine-readable syntax that IDEs can use for code completion and linting of your code.

We do not have information about the type of the parameters that Member takes.

password is probably a string, but what about id? Is it a string, or a number? Not even by looking at the function can we tell. We do know, from looking at the example usage that the designer intends it to take a string.

But how can we communicate that to consumers of the function, and preferably at the point they are using it, rather than requiring them to find the declaration and read a comment there?

With TypeScript, you can annotate the types on the function signature:

If you are not using TypeScript, you can use JSDoc comments to provide this metadata, and good IDEs will make use of it.

Annotating destructured parameter signatures is a little tricky, but here is how you do it for this function.

Remember that I said that the destructured assignment takes an anonymous object?

Well, in the JSDoc comment, we have to name the object in order to be able to name and describe its properties:

While we are at it, we can annotate the function to communicate to both the machine (IDE linting) and humans that the function must be newed. This takes our naming by convention to another level, because good IDEs will be able to a consuming programmer that they forgot to new our function, if they forget.

To do that, we use the JSDoc @constructs annotation.

Finally, we can also supply information about the new object that gets returned. This provides consumers with information not only about the API surface of our function, but information about the object they create with it.

IDEs and linting tools can use this to provide auto-completion and catch bugs related to instances of Member objects that consumers create.

We use the JSDoc @typedef and @property annotations to do this:

At this point, a good IDE knows exactly what is going on, and can provide intelligent guidance to consumers of your API:

The IDE knows that I have an instance of a Member object, and it knows about the name and type of each of its properties. (The theme is Synthwave and the font JetBrains Mono if you were wondering.)

#winning

You can also have ESLint running in CI, for example in a GitHub Actions Workflow, to catch bugs relating to the use of this API, before they hit production.

Using TypeScript

Honestly though, writing that much JSDoc is a pain. One of the issues with it is that it is possible to refactor the function and not update the JSDoc. You have to do double the work to make sure they stay in sync.

Especially when you are prototyping, you don’t want to add that much overhead. But you would like the safety and IDE assist that you get from it.

In that case, you want TypeScript. The IDE autocompletion and type-safety is directly tied to the inline declaration of types, and not to a decoupled description that you have to write.

Unless you are firmly wedded to using plain JS, TypeScript is a better solution. With automatic type definition generation, you can provide code that JS programmers can consume with typings that their IDE can use.

Resources

About me: I’m a Developer Advocate at Camunda, working primarily on the Zeebe Workflow engine for Microservices Orchestration, and the maintainer of the Zeebe Node.js client. In my spare time, I build Magikcraft, a platform for programming with JavaScript in Minecraft.