Implementing a Maybe Pattern using a TypeScript Type Guard

Taking inspiration from the Maybe monad to enforce run-time null-safety while coding in TypeScript.

You’re sat at a restaurant, and you order a beer. The waiter disappears into the kitchen, and returns a couple of minutes later, empty-handed. “I’m sorry,” he says. “I could not get your beer.”

Now here is the six-million dollar question: is the restaurant out of the beer that you ordered (business logic), or is the restaurant kitchen on fire (infrastructure failure)?

And how do you model those two distinct failure states in your API? (Credit to Kory Nunn for the restaurant metaphor).

Recently, I was working on a database library in TypeScript. It provides a strongly-typed abstraction over stored procedures to allow the application to declaratively interact with the data model without leaking the implementation details.

In this way we can implement caching, and even switch out the database without any change to the application logic or unit tests — which are easy to write because we can mock the data layer interface.

I took inspiration for this approach from a workshop I attended with Mark Seeman at NDC Sydney this year. In that workshop, we looked at modelling multiple return states using monoids.

Success and Failure: not a Binary State

A database call to retrieve a record may succeed or fail. It may fail to retrieve anything due to a fatal exception — like a database going away. If the database call succeeds, however, we have two states that we need to represent: either “here is the record”, or “no record was found”. So we have three states that we need to represent: fatal exception, success with data, and success with no data.

These can be thought of as a failure mode (infrastructure failure), a success mode, and a mixed success/failure mode (infrastructure success / application data failure). Kory Nunn describes the issue of the nuanced states like this: I go to a restaurant and order a beer. The waiter goes to the kitchen and then comes back and says: “I’m sorry, I couldn’t get you a beer.”

The issue here is: Why couldn’t you get me a beer? Are you out of beer (no record found)? Or is the kitchen on fire (database disappeared)?

This is a collapse between the two possible failure modes. Kory has developed the Righto library for lazily evaluating asynchronous operations and modelling these two failure states.

For this library, however, we took a different approach, taking inspiration from the Maybe monad.

The Kitchen Is Definitely On Fire!

First, we model database failures as exceptions. If the kitchen is on fire, we throw. This will interrupt the application logic flow, and it is the responsibility of the caller to handle this. If the kitchen is on fire, stop the action.

If the kitchen is not on fire, however, we need to model two states: we got a record back (“here is your beer!”), or there was no matching record found (“sorry, we’re all out of Fosters lager. Actually, we don’t stock it in Australia.”).

A simple way to do this is to test the return from the database call to see if it is null. However, this cannot be checked statically, as it relies on the runtime return value. We also can’t enforce that a developer handle this case (with one caveat that I will address).

The Kitchen Isn’t On Fire — This May Be Your Beer, Or Not…

So we implement the return value as a MaybeRecord — maybe you got a record back, and maybe not.

We can use TypeScript’s type guards to enforce handling both cases. There are TypeScript Maybe Monad implementations, like TS-Monad. However, these burden developers with a verbose syntax that obscures the code.

As an example, here is some idiomatic JavaScript where the developer tests for a value before attempting to use it:

if (age) {

var busPass = getBusPass(age); // might be null or undefined

if (busPass) {

canRideForFree = busPass.isValidForRoute('Weston');

}

}

Here’s my caveat from earlier: if you use strict null checking and define the return signature of getBussPass() as BussPass? or BussPass | undefined, then you will get an error that busPass may be undefined. You can use a type guard on this, but your intent is not explicit.

With the TS Monad, you write this as:

var canRideForFree = user.getAge()

.bind(age => getBusPass(age))

.caseOf({

just: busPass => busPass.isValidForRoute('Weston'),

nothing: () => false

});

It’s explicit, but verbose — and not idiomatic JavaScript or TypeScript. Not ideal.

Using the TypeScript Type Guard to Type “Maybe”

We used TypeScript’s literal types and type guards to build a Maybe pattern. It is not a monad — it is not composable — but it does provide us with null safety and forces the application developer to think about the logic around the two success states.

We defined the signature of our method as MaybeRecord where:

type MaybeRecord = Record | RecordNotFound

We then define the two types like this:

class RecordNotFound {

found: false = false;

}

class Record {

found: true = true;

name: string;

age: number;

constructor(name: string, age: number) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

}

In the method implementation we return either new RecordNotFound() or new Record(res.name, res.age).

Then in the consuming code, the return value has only the intersection property found. So if we make a small test implementation:

function returnMaybeRecord(exists: boolean): MaybeRecord {

if (exists) {

return new Record('Joe Bloggs', 42);

} else {

return new RecordNotFound();

}

}

We can see what happens in VSCode when we do this:

const maybeExists = Math.random() > 0.5;

const maybeRecord = returnMaybeRecord(maybeExists);

The only property that reliably exists on the returned value is found. If we now write a type guard:

if (maybeRecord.found) {

}

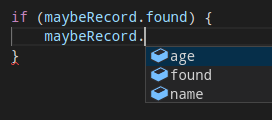

And now, inside the type guard we have a Record:

This enforces in the application that the maybeRecord must be explicitly checked before it can be used.